The Loss Given Default Ratio - What It Is And How To Calculate It

- Analyst Interview

- Jun 7, 2023

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2024

The Loss Given Default Ratio: A Comprehensive Guide

The Loss Given Default (LGD) Ratio is critical in credit risk analysis, helping lenders evaluate potential losses from defaulting loans. This guide provides an in-depth look at its calculation and significance.

In today’s financial markets, where the complexities of risk management continue to grow, understanding the Loss Given Default (LGD) ratio is essential for finance professionals, particularly those in credit risk management. Whether you are a banker assessing a new loan or an investor evaluating potential returns on risky assets, the LGD ratio helps quantify the percentage of a loan or asset's value that may be lost if the borrower defaults. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve deep into what LGD is, how it's calculated, its importance in credit risk analysis, and how financial institutions use it to safeguard their interests.

What Is the Loss Given Default Ratio?

At its core, the Loss Given Default (LGD) ratio is a metric used in credit risk analysis to estimate the potential loss a lender may face if a borrower defaults on a loan. In other words, it measures the severity of a financial loss in the event of a default. LGD is typically expressed as a percentage of the total loan exposure at the time of default and represents the actual financial loss incurred after considering recoveries such as collateral liquidation or insurance payouts.

For example, if a borrower defaults on a loan of $100,000 and the lender manages to recover $40,000 through collateral sales, the LGD would be 60%—the unrecovered portion of the loan.

Importance of LGD in Credit Risk Analysis

The LGD ratio plays a critical role in credit risk management for both lenders and investors. Here's why:

Risk Assessment: LGD is a key component in calculating Expected Loss (EL), which is the product of Probability of Default (PD), Exposure at Default (EAD), and LGD. This calculation is used to estimate potential future losses from lending portfolios, helping financial institutions make informed decisions.

Capital Allocation: LGD is crucial in determining how much capital a bank or financial institution needs to allocate to cover potential loan losses. Regulators often require banks to maintain a certain level of capital reserves based on the risk profiles of their lending portfolios, which LGD helps define.

Loan Pricing: By understanding the potential losses a lender may face, the LGD ratio helps in the pricing of loans. Higher LGD values suggest a higher risk, which could result in higher interest rates charged to borrowers to compensate for that risk.

Credit Risk Mitigation: LGD can be mitigated through collateral management, effective credit monitoring, and other credit enhancement techniques. Understanding LGD allows lenders to take proactive measures to reduce the severity of losses in the event of defaults.

Factors Affecting the Loss Given Default Ratio

Several factors can influence the LGD ratio, making it a dynamic component of credit risk analysis. These factors include:

Collateral Value: The presence and quality of collateral are key in determining LGD. The higher the value of the collateral relative to the loan, the lower the LGD. However, factors like market volatility and legal costs associated with liquidating collateral can affect recoveries.

Loan Structure: The terms of the loan, including its maturity, interest rate, and repayment schedule, can influence the severity of a loss. For example, a shorter-term loan with higher interest payments may result in lower LGD due to faster paydown.

Recovery Timeframe: The speed at which a lender can recover funds after a default impacts LGD. The longer it takes to recover funds, the higher the potential loss, especially when considering time value of money and legal expenses.

Economic Environment: Broader economic conditions such as recessions or market downturns can affect the recoverability of loans. During economic slowdowns, asset values (including collateral) may fall, leading to higher LGDs.

Borrower Characteristics: The financial health of the borrower, their business prospects, and their ability to generate cash flows also impact LGD. A financially distressed borrower may have fewer assets available for recovery.

How to Calculate Loss Given Default (LGD)

Calculating LGD is relatively straightforward in principle but can be complex in practice, depending on the availability of data and the specific recovery mechanisms in place. The basic formula for LGD is:

LGD (%) = (Total Loss on Exposure / Total Exposure at Default) * 100

Here’s a simplified example:

Loan Amount: $100,000

Recoveries from Collateral Sale: $30,000

Total Loss: $100,000 - $30,000 = $70,000

LGD = ($70,000 / $100,000) * 100 = 70%

In this case, the lender's LGD is 70%, meaning 70% of the loan value was lost due to the default.

However, calculating LGD in real-world scenarios can involve multiple complexities:

Collateral Valuation: If the loan is secured by collateral, the value of that collateral may fluctuate over time, especially in volatile markets like real estate or commodities.

Legal and Administrative Costs: Recovering funds through the courts or legal proceedings can add significant costs, further increasing LGD.

Time Value of Money: The delay in recovering funds means that the present value of those recoveries must be considered.

In practice, LGD can also be broken down into two categories: LGD before recoveries (gross LGD) and LGD after recoveries (net LGD). Gross LGD looks at the initial loss at default, while net LGD considers the actual amount recovered over time.

Types of LGD Models

To accurately predict LGD, financial institutions often use statistical models. These models can be broadly classified into two categories:

Direct Estimation Models: These models estimate LGD directly based on past historical data of defaults and recoveries. Commonly used statistical techniques in these models include regression analysis, machine learning algorithms, and decision trees.

Indirect Estimation Models: Indirect models, also known as structural models, estimate LGD based on the characteristics of the loan, the borrower, and macroeconomic conditions. These models may factor in variables such as credit rating, collateral type, and market volatility.

Financial institutions often customize these models based on their portfolios, using a combination of data-driven insights and expert judgment.

Examples

Here are five real company examples from various sectors, illustrating different scenarios for LGD calculations.

1. Company A: Retail Sector

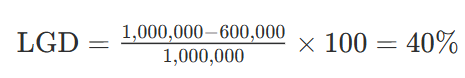

EAD: $1,000,000

Recovery Amount: $600,000

Calculation:

Interpretation: In the retail sector, Company A faces a 40% loss given default, indicating that it can recover 60% of its exposure, which is relatively favorable in a sector often affected by economic downturns.

2. Company B: Real Estate Sector

EAD: $2,500,000

Recovery Amount: $1,000,000

Calculation:

Interpretation: Company B in the real estate sector has a 60% LGD, suggesting that the recovery rate is low, possibly due to declining property values or market conditions affecting real estate sales.

3. Company C: Technology Sector

EAD: $750,000

Recovery Amount: $500,000

Calculation:

Interpretation: Company C's LGD of 33.33% indicates a relatively strong recovery rate of 66.67%, which is typical in the technology sector where assets may retain value even after default.

4. Company D: Manufacturing Sector

EAD: $1,200,000

Recovery Amount: $300,000

Calculation:

Interpretation: With a 75% LGD, Company D in manufacturing faces significant losses upon default, indicating poor asset recovery, possibly due to high fixed costs and depreciation of machinery.

5. Company E: Financial Services Sector

EAD: $3,000,000

Recovery Amount: $2,700,000

Calculation:

Interpretation: Company E has a very low LGD of 10%, reflecting a strong recovery rate of 90%. This is common in financial services where collateralized loans often lead to higher recovery rates.

Basel II and III Regulations on LGD

The Basel Accords, which set international standards for banking regulation, have placed significant emphasis on LGD. Under Basel II and Basel III, financial institutions are required to calculate their risk-weighted assets (RWAs), which take into account PD, EAD, and LGD. The goal is to ensure banks maintain sufficient capital to cover potential losses.

Basel II introduced the concept of Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) Approaches, allowing banks to develop their own LGD models subject to regulatory approval. This framework provided banks with greater flexibility in managing risk but also increased the need for accurate LGD calculations to avoid underestimating credit risks.

Challenges in Estimating LGD

Estimating LGD can be challenging due to various factors:

Data Availability: LGD estimates require historical default and recovery data, which may not always be available, particularly for smaller financial institutions or new loans.

Market Volatility: Collateral values can fluctuate significantly in volatile markets, leading to unpredictable recovery rates and, consequently, unstable LGD estimates.

Legal and Recovery Costs: Estimating the costs associated with legal proceedings, enforcement, and asset liquidation can be difficult, further complicating LGD predictions.

Time Lag in Recovery: Recoveries may take years to materialize, making it challenging to discount future cash flows accurately.

Despite these challenges, advancements in data analytics and machine learning are improving the accuracy of LGD models, helping financial institutions better estimate potential losses.

Loss Given Default Ratio vs Other Ratios

LGD vs. Probability of Default (PD)

One of the most important ratios often discussed alongside LGD is the Probability of Default (PD). While both are critical in credit risk analysis, they measure entirely different aspects of risk.

Definition of PD: PD estimates the likelihood that a borrower will default on a loan within a specific time frame, often one year. It’s expressed as a percentage and reflects the borrower's creditworthiness.

Key Differences:

PD is about the chance of default, whereas LGD measures the severity of loss after the default occurs.

PD is forward-looking and linked to the borrower's characteristics, like credit score, financial health, and market conditions. LGD, on the other hand, focuses on recovery after a default, accounting for collateral and recovery processes.

How They Complement Each Other:PD and LGD are used together to calculate the Expected Loss (EL), which is a cornerstone of credit risk management:

Expected Loss (EL) = PD × LGD × EAD

This formula shows how the likelihood of default (PD) interacts with the extent of loss (LGD) and the exposure at default (EAD) to give a comprehensive measure of risk. While PD gives insight into whether a loss might happen, LGD tells us how much might be lost if it does.

LGD vs. Exposure at Default (EAD)

Exposure at Default (EAD) is another important metric in credit risk that often gets confused with LGD. Here's how they differ:

Definition of EAD: EAD represents the total value that is exposed to default risk at the time the borrower defaults. This could include the principal loan amount, interest payments, and other financial exposures like lines of credit.

Key Differences:

EAD is the exposure at risk, while LGD focuses on the net loss after recoveries.

EAD is usually determined before the borrower defaults, based on loan contracts and available credit. LGD, on the other hand, is calculated after a default event, focusing on how much of that exposure is lost.

How They Work Together:EAD is a crucial input for calculating both the Expected Loss (EL) and the Capital at Risk. LGD defines how much will be lost if the borrower defaults on the EAD. If the EAD is high but LGD is low (due to strong collateral), the overall risk may be manageable.

LGD vs. Recovery Rate (RR)

The Recovery Rate (RR) is often described as the flip side of LGD. Where LGD calculates what is lost, RR measures what is recovered:

Definition of RR: RR is the percentage of the loan amount recovered after a default. It is essentially the opposite of LGD and is given by the formula:

RR = (Amount Recovered / Exposure at Default) × 100

Key Differences:

LGD and RR are inversely related. If a loan has an LGD of 70%, the RR will be 30%.

While LGD is more commonly used in risk assessments, RR is useful for understanding the effectiveness of recovery efforts, including collateral liquidation, restructuring, or bankruptcy proceedings.

How They Work Together:Both metrics are essential for lenders to estimate the true impact of defaults. A higher RR means better recovery prospects, resulting in a lower LGD, and thus, reduced financial risk.

LGD vs. Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR)

The Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) is a regulatory measure used to ensure that banks maintain adequate capital reserves to cover their risks, including credit risk. Here’s how CAR and LGD compare:

Definition of CAR: CAR is the ratio of a bank's capital to its risk-weighted assets (RWAs). It ensures that a bank has enough capital to absorb losses while continuing to operate.

Key Differences:

CAR is a macro-level measure that looks at the overall health and capital sufficiency of a bank, while LGD focuses specifically on the micro-level loss from individual defaults.

While LGD helps calculate specific loan risks, CAR assesses the broader financial stability of a bank in relation to all its risk exposures.

How They Relate:LGD plays a role in determining the credit risk component of a bank's risk-weighted assets (RWAs), which are part of the CAR calculation. A high LGD increases the capital a bank must hold, lowering its CAR. Therefore, accurate LGD estimation is critical to maintaining healthy CAR levels and regulatory compliance under Basel III guidelines.

LGD vs. Debt-to-Equity Ratio (D/E)

The Debt-to-Equity (D/E) Ratio is another key financial metric, especially in corporate finance, that compares a company’s total debt to its equity. Here's how it contrasts with LGD:

Definition of D/E Ratio: The D/E ratio measures a company’s financial leverage by dividing its total liabilities by its shareholder equity. It shows how much debt a company is using to finance its operations relative to equity.

Key Differences:

The D/E ratio is a balance sheet measure that reflects a company’s capital structure, whereas LGD focuses on credit risk and the potential loss from a default event.

The D/E ratio is concerned with a company’s overall financial health and its ability to meet its obligations, while LGD looks at the specific losses a lender might face on a defaulted loan.

How They Complement Each Other:While the D/E ratio gives investors and creditors a sense of a company’s leverage, LGD is more relevant for lenders when evaluating the specific risk of a loan or credit facility. A highly leveraged company (high D/E ratio) may have a higher Probability of Default (PD), making the LGD more critical for lenders in pricing the risk.

LGD vs. Loan-to-Value Ratio (LTV)

In the world of secured lending, especially mortgages, the Loan-to-Value (LTV) Ratio is a common metric. Here's how it compares to LGD:

Definition of LTV Ratio: LTV measures the ratio of a loan amount to the value of the collateral securing the loan. A lower LTV ratio suggests lower risk for the lender since the collateral is worth more than the loan.

Key Differences:

LTV is a pre-default measure focused on the relationship between loan size and collateral value, while LGD is a post-default measure assessing how much of the loan is lost after default.

LTV is used to assess the risk of issuing a loan, particularly in real estate, whereas LGD comes into play after a default, measuring the potential financial loss.

How They Relate:Loans with a lower LTV ratio typically have a lower LGD because the collateral covers a larger portion of the loan. In contrast, high LTV loans might lead to higher LGDs due to insufficient collateral to cover the loan balance in case of default.

FAQs

What is the Loss Given Default ratio?

The Loss Given Default ratio is a measure of the potential loss a lender may face when a borrower defaults on a loan, expressed as a percentage of the total loan exposure.

How is LGD calculated?

LGD is calculated by dividing the total loss on a loan by the total exposure at default and multiplying by 100. It represents the unrecovered portion of the loan after default.

Why is LGD important for banks?

LGD helps banks assess potential loan losses, allocate capital reserves, and price loans appropriately. It is also a critical factor in regulatory capital requirements under the Basel Accords.

What factors influence LGD?

Several factors influence LGD, including the value of collateral, loan structure, recovery timeframe, borrower characteristics, and economic conditions.

How can financial institutions reduce LGD?

Financial institutions can reduce LGD by improving collateral management, monitoring borrowers' financial health, restructuring distressed loans, and streamlining legal recovery processes.

What is the role of LGD in credit risk modeling?

LGD plays a crucial role in credit risk modeling as it helps estimate the expected loss from defaults. It is used in conjunction with Probability of Default (PD) and Exposure at Default (EAD) to calculate total risk exposure.

Conclusion

The Loss Given Default ratio is a vital component of credit risk analysis, providing essential insights into the potential financial losses associated with defaults. By understanding and calculating LGD, lenders and financial institutions can make more informed decisions, allocate capital more efficiently, and mitigate risks effectively. As the financial landscape continues to evolve, the importance of LGD in risk management will only grow, underscoring its significance in maintaining financial stability.

-min.png)

-min.png)

Comments